Open Ideas; a refactor of free speech

It's time to reframe freedom of speech to return to its foundations

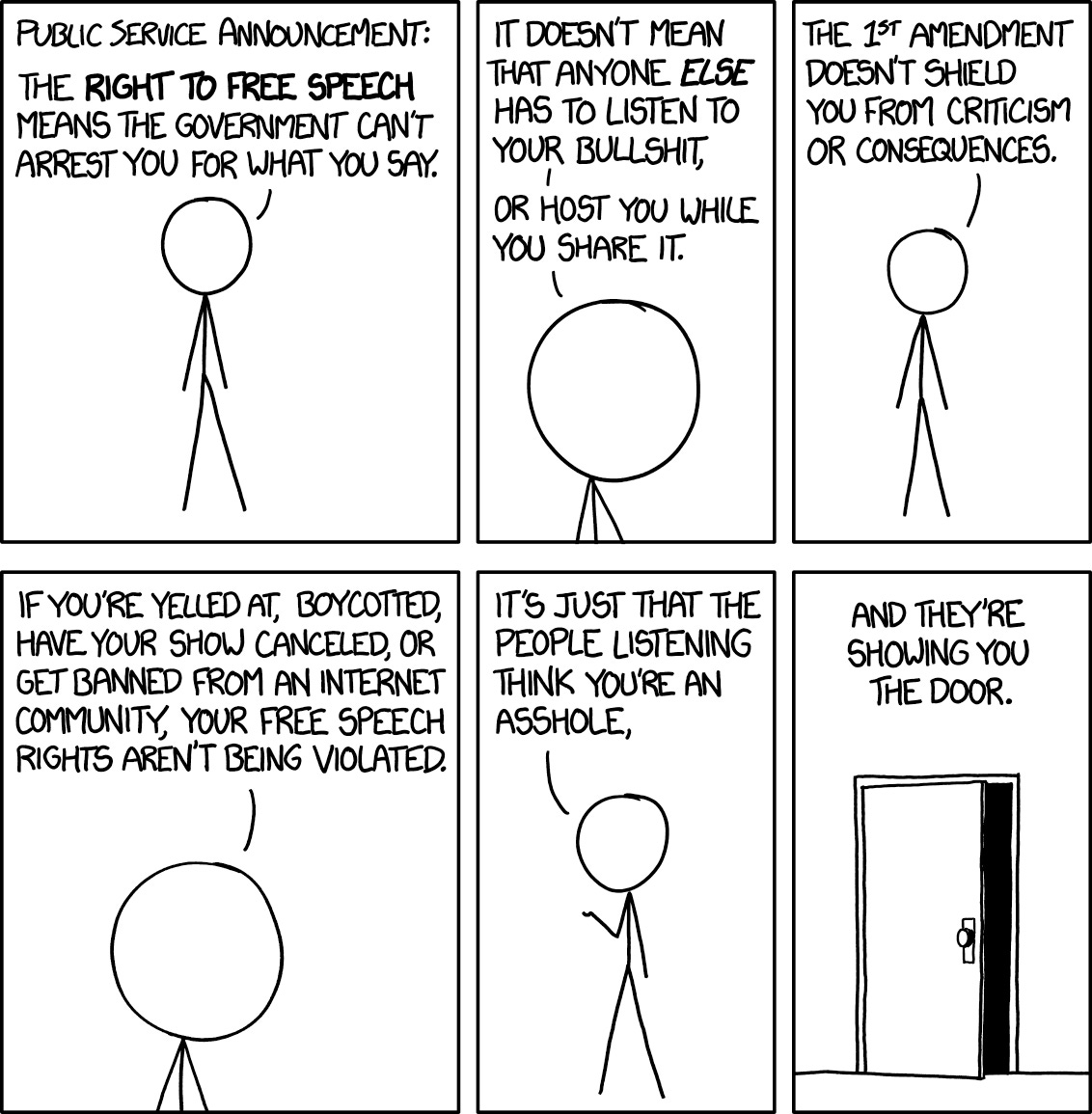

Modern debate is not what it used to be. In the past entire books were written to argue a point, today people believe the whole philosophical underpinnings of freedom of speech can be exposed in a cartoon. Needless to say a lot of nuance is lost.

I’ve written before on the fatal equivocation fallacy that is to conflate freedom of speech with the First Amendment. People equate one with the other, and although they are related, they are not the same. This creates a problem so catastrophic that I believe the First Amendment is actually destroying what’s left of freedom of speech.

My claim is that the modern notion of freedom of speech conflates two distinct ideas: an individual right and an engine of progress. Both may be important, but great thinkers of the past argued mostly in terms of freedom of speech being an engine of progress, and today people consider freedom of speech solely as an individual right, which although important, it pales in comparison to the necessity of societies to keep ideas open.

Now I’m not a great thinker (at least not a renowned one), so most people are going to dismiss my ideas, which is fine. So before trying to change the status quo, let’s explore what great thinkers of the past argued about freedom of speech in order to see how far we’ve deviated.

Great thinkers

Milton

“Let her [Truth] and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter?”

— John Milton (Areopagitica, 1644)

Milton believed that truth must be kept alive through struggle. In Areopagitica he pictured Truth and Falsehood grappling in “a free and open encounter,” warning that without such trials truth weakens. He likened truth to a “living fountain”, which must flow freely rather than be muddied or dammed by authority. To censor speech is to mistrust truth’s strength and to risk reducing it to something brittle and corrupted — not a living force guiding society, but a relic untested by reality.

Voltaire

“It is by the free clash of opinions that truth is established.”

— Voltaire (paraphrased from Philosophical Dictionary, 1764):

Voltaire saw the “clash of opinions” as the safeguard against intellectual stagnation. He argued that progress is not the product of rulers dictating dogma, but of vigorous exchange in which ideas collide and refine one another. Without this clash, even true beliefs sink into lifeless repetition. Authority that stifles debate does not protect truth but condemns it to stagnation, making it incapable of guiding a society forward.

Kant

“The public use of reason must always be free, and it alone can bring about enlightenment among men.”

— Immanuel Kant (What is Enlightenment?, 1784)

Kant warned of the danger of immaturity when reason is not given free rein. In What is Enlightenment? he insisted that the “public use of reason” must remain free, for only then can humanity progress from dependence to self-rule. When individuals are denied the chance to argue openly, they remain trapped in passive acceptance of formulas handed down by authority. Reason then ceases to be a living, critical force and becomes empty recitation — a kind of intellectual stagnation that blocks enlightenment.

Tocqueville

“The circulation of ideas keeps society from sinking back into ignorance.”

— Alexis de Tocqueville (Democracy in America, 1835–40)

Tocqueville viewed freedom of the press as democracy’s indispensable safeguard. In his eyes, majorities tend toward conformity, and without a free press and free discussion, societies slide into intellectual monotony. Where opinions are not challenged, they harden into collective dogma, leaving citizens passive and progress halted. The press, though imperfect, constantly shakes received wisdom, ensuring that ideas remain contested and that society avoids the stagnation of thought that democracy’s very equality otherwise encourages.

Mill

“The liberty of thought and discussion is the only safeguard of the mental well-being of mankind, and the source of every other liberty which is of value.”

— John Stuart Mill (On Liberty, 1859)

Mill developed the point most systematically in On Liberty. He argued that to suppress an opinion, whether true or false, is to rob society of vitality: if true, we lose correction of error; if false, we lose the sharper understanding of truth gained by refuting it. More dangerously, when truths go unchallenged they degenerate into what Mill called “dead dogma” — beliefs repeated without comprehension or conviction. Only through the continual collision of opinions can truth remain a living power and society avoid the stagnation of thought.

Popper

“The freedom of thought, and therefore the freedom of speech, is the basis of scientific progress.”

— Karl Popper (The Open Society and Its Enemies, 1945)

Popper carried the Enlightenment rationale into the modern age of science. He argued that knowledge advances only through criticism — through conjectures tested by attempts at refutation. When speech is suppressed, error becomes entrenched, and even true theories ossify into unquestioned dogma. Free criticism keeps science and society alive, because it prevents stagnation and forces even the best ideas to justify themselves continually. For Popper, open discussion is not just a political liberty but the very mechanism by which humanity learns and improves.

Today thinkers

Let’s compare what the great thinkers said in the past, with what modern thinkers say today:

“The right to free speech means the government can’t arrest you for what you say. It doesn’t mean that anyone else has to listen to your bullshit, or host you while you share it.”

— Randall Munroe (XKCD, 1357)

All the great thinkers of the past argued in terms of what freedom of speech ought to be, and more importantly: why.

Milton, Voltaire, Kant, and Mill saw free expression not as a mere personal privilege but as society’s engine of progress — the mechanism by which truth is tested, refined, and kept alive. Milton imagined Truth and Falsehood grappling openly, warning that sheltering ideas from challenge weakens them. Voltaire emphasized the clash of opinions, showing that without vigorous exchange even correct beliefs stagnate into lifeless dogma. Kant framed freedom of reason as essential for enlightenment itself: when people are barred from debating and publishing their thoughts, society remains trapped in immaturity and intellectual dependence. Mill made explicit the danger of “dead dogma”, arguing that unchallenged truth loses its vitality, while confronting error keeps ideas alive and society advancing.

Across these perspectives, the message is clear: suppression of speech does not protect society but imperils its capacity to grow, learn, and progress.

Instead of quoting any of these great thinkers, people today quote Munroe, who is not providing any argument or consideration for what could happen to society. Instead Munroe repeats what he believes freedom of speech is (not ought to be), based on the legislation of his country, and there’s no rationale as to why.

This is the antithesis of what freedom of speech was supposed to be. We shouldn’t be repeating the established dogma, we should be questioning freedom of speech itself — or in this case what people today wrongly believe freedom of speech to be.

The fatal fallacy

It should be clear now why I argue that conflating freedom of speech with the First Amendment is such a catastrophic mistake.

According to the great thinkers, freedom of speech was supposed to mainly benefit society, as an engine of progress, and a tool for truth discovery, and it’s society the one that should be defending it. The First Amendment came along to protect an individual right, but its primary purpose was to prevent government tyranny. It’s narrow in scope, because by definition it has to be. Society must still protect freedom of speech for its own benefit.

Instead, societies are now relinquishing this duty and relegating it to the government, which by definition it cannot do.

Let’s consider one quote of Mill:

“If all mankind minus one were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind.”

— John Stuart Mill (On Liberty)

How is the USA government supposed to enforce that if say for example one person utters a detestable opinion in a university campus stand that everyone else disagrees with and therefore wish the silence him?

It’s not the government’s job to defend freedom of speech. It’s you, and me, and everyone else.

So the First Amendment is irrelevant (not to mention only applicable in one country on the planet).

Muddied

How can we go back to the intended meaning of freedom of speech (engine of progress)? In my personal experience, it would be easier to unscramble an egg.

The term has already been muddied, and there’s no argument that people today — who hardly have opened a book in the past decade — would be willing to listen.

Simply put: freedom of speech is what everyone says freedom of speech is.

It doesn’t matter that great thinkers of the past would consider this position dead dogma, and the antithesis of freedom of speech.

People today just repeat the slogan “freedom of speech doesn’t mean freedom from consequences”. Which great thinker came up with that? No one. It materialized from the either and has absolutely zero philosophical rationale. This is a catchy slogan used to justify all kinds of social censorship, which is precisely what actual great thinkers warned about.

But try as one might, I haven’t been able to convince anyone that freedom of speech should mean freedom from consequences.

It seems you can’t unring a bell.

Solution

In my estimation, therefore the solution is to come with a new term that encompasses what the great thinkers argued for (an engine of progress), and the best I could come up with is: Open Ideas.

Open Ideas retains the core principle of what great thinkers argued should be the reason for freedom of speech: without open contestation of ideas, society stagnates.

This isn’t just an article, it’s the beginning of a whole project to reframe freedom of speech as Open Ideas.

The link to the work in progress project is this: Open Ideas.

So far I’ve come up with a manifesto, a rationale, a couple of slogans, and more. But it does need help.

Personally I don’t see any other way for society to reclaim its duty to defend freedom of speech in terms of what it should be: an engine of progress that benefits society itself.